Introduction to the Study Grammar¶

Written by Noah Nelson

Noah Nelson is VP of Product and has volunteered at FindingFive since 2017. He has a PhD in Linguistics from the University of Arizona.

The FindingFive Study Grammar is like a simple coding language for building experiments and rendering them to participants. It is based on JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). If you are not familiar with JSON, it may be helpful to review our JSON tutorial first.

There are a few key differences between standard JSON and the FindingFive Study Grammar. We will discuss those differences along with some general points of interest for using the Study Grammar below.

How does the FindingFive Study Grammar work?

FindingFive runs on the web, meaning that your experiments are ultimately rendered from HTML, CSS, and JavaScript code. The FindingFive Study Grammar is like a translation algorithm that takes simple JSON-based code written by researchers as an input and generates the necessary HTML, CSS, and JavaScript code as an output.

The FindingFive Study Editor Page¶

Before we begin discussing the Study Grammar, let's get acquainted with the study editor page. This is where you will input the JSON-based code used for the Study Grammar.

The study editor contains four top-level sections:

- Stimuli—where stimuli are defined

- Responses—where responses are defined

- Trial Templates—where trial templates are defined, which build and organize trials

- Procedure—where blocks of trials are defined and ordered

As you can see, each of these sections is where a different kind of object is defined: stimuli, responses, trial templates, and blocks.

Why are they called top-level sections?

The FindingFive Study Grammar is divided into these four sections, which are ultimately stitched together to form an experiment. Each section contains an arbitrary number of lower-level FindingFive objects. Because these sections define the highest level at which the researcher can edit a study, we call them “top-level”.

FindingFive Objects¶

FindingFive objects are JSON objects, each consisting of a collection of property-value pairs. However, there are a few additional features of FindingFive objects to be aware of.

Object Names¶

Every FindingFive object (stimulus, response, trial template, or block) gets a user-defined name. This name exists outside the collection of property-value pairs that specify the attributes of that object. For trial templates and blocks, objects are defined using the format "name": {<definition>}, where the name is like a user-defined property and the definition is its value.

"my_trial_template": {

"type": "basic",

"stimuli": ["stim1", "stim2", "stim3"],

"responses": ["resp1"]

}

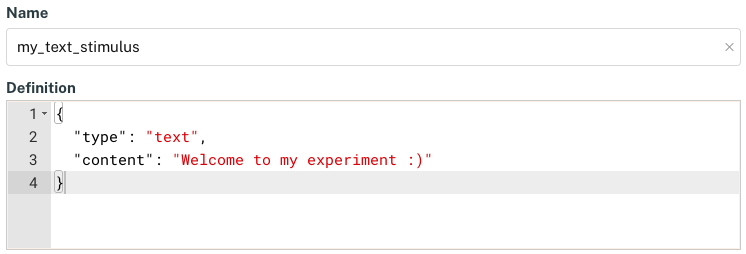

In the case of stimuli and responses, the study editor interface prompts you to input the object's name and definition as separate fields in a popup, but the underlying logic is the same.

FindingFive objects include both a name and a definition.

Object Properties¶

Required Properties¶

In the FindingFive Study Grammar, every object has some number of required properties. These are properties that have no default value and must be specified in each object instance. The specific properties that are required depend on the particular object.

For example, stimuli have required properties for "type" and "content". This is the minimal information required for our code parser to determine how to present each stimulus. By contrast, responses have a required property for "type" only, as some response types can be presented without further information.

What is a code parser?

A code parser is a set of scripts that take simplified inputs (such as our JSON-based Study Grammar code) and interpret them as more robust logical objects. For example, the FindingFive parser expects a "type" property for all objects, and uses this to determine what additional information it needs to represent the object. If the "type" property is missing or has an incorrect value, the parser will present an error to the user.

Non-required Properties and Default Values¶

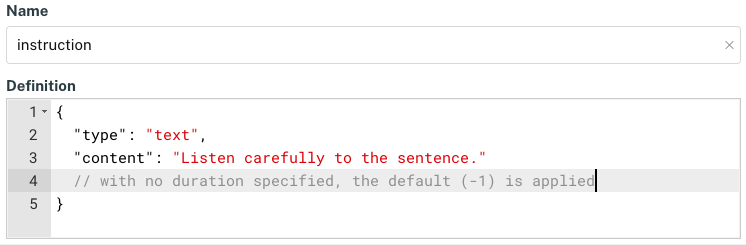

Every object also has additional properties that are not required. This does not mean that the properties do not have a value, however. Instead, it means that there is a default value used by the Study Grammar. If you choose not to specify that property, the default value will be applied. This is known as default by omission. If you choose to, however, you can always change that default value by specifying the property-value pair explicitly.

For example, every text or image stimulus object has a "duration" property allowing you to specify a presentation duration for the stimulus. By default, the value of that property is -1, which causes the stimulus to be displayed indefinitely until something else triggers the end of the trial (such as a participant clicking a continue button).

An example text stimulus with no duration specified, leading to the default value (-1).

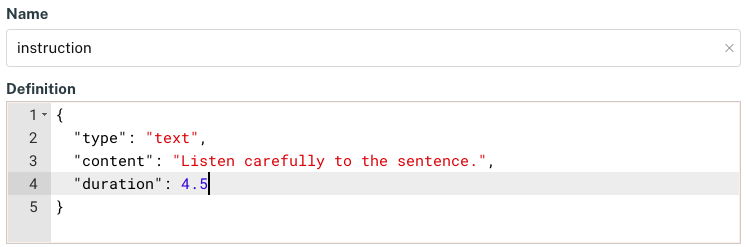

This behavior may be desired for some things, such as instructions to participants or when stimulus duration is best handled at the trial level. However, in many other cases you may want to control precisely how long a stimulus is presented to participants, and so you will want to override that default by specifying your own value for the "duration" property.

An example stimulus with a specified duration of 4.5 seconds (4500 ms).

Properties and defaults vary by object type

We noted above that text and image stimulus objects have a default duration of -1, but FindingFive can handle several other types of stimuli as well, including audio and video stimuli. However, since these have an inherent duration, no default value is applied by the Study Grammar for the "duration" property (but you can still specify it explicitly). This reflects the general design of the Study Grammar, which aims to be as intuitive as possible while providing maximum flexibility to the researcher.

Custom (User-defined) Properties¶

In general, each object has a set of pre-determined properties defined by the Study Grammar and recognized by our code parser. However, there are a few cases where you as the researcher can define your own object attributes. These are custom properties that you name yourself and give any value that you want. For example, you can define custom properties for stimuli that can then be used to perform advanced trial ordering or pseudorandomization.

Ignored properties

Technically, you can add your own custom properties to any object in the FindingFive Study Grammar. However, these custom properties wiill generally be ignored by the parser. Only in select cases noted in the Study Grammar reference—such as custom stimulus properties or custom meta data columns in trial templates—will these custom properties carry any meaning for the definition of your experiment.

Property Formatting¶

As with all JSON objects, FindingFive objects are built of one or more property-value pairs that must follow these formatting rules:

- the property is always written as a string, enclosed in double quotes

- the property is always followed by a colon, then the value

For example, note how the property “stimulus_pattern”: {...} conforms to these general rules for JSON object properties. Any user-defined property or object name must also conform to these rules.

Additional conventions apply to pre-defined properties of FindingFive objects. Specifically, in addition to enclosing them in double quotes followed by a colon, properties of FindingFive objects:

- are always fully lowercase (no capital letters)

- each word is separated by an underscore

_when a property includes multiple words

Note how the property “stimulus_pattern”: {...} also conforms to these more specific conventions for pre-defined object properties. However, user-defined property or object name need not follow these more specific conventions.

Comments¶

Unlike standard JSON, the FindingFive Study Grammar supports the use of comments. Comments are lines in your code that will be ignored by the code parser. This is useful for making notes to yourself or collaborators, organizing sections of your code, or "commenting out" lines of code without completely deleting them (which is itself useful for debugging errors). Presently, comments are only preserved in the Trial Templates and Procedure sections of the study editor.

To add a comment, simply prepend // before the comment content. Comments can begin anywhere on any line, but they necessarily apply to the remainder of that line. For example:

// This is a comment. It lasts until the end of this line.

"my_trial_template": {

"type": "basic",

"stimuli": ["stim1", "stim2", "stim3"],

"responses": ["resp1"] // this is also a comment

}

Block comments

The FindingFive Study Grammar does not support so-called "block comments", which is a way of commenting out an entire multi-line code block without commenting out each individual line (e.g., /*...*/ in JavaScript). However, a commenting hotkey (CTRL-/ or CMD-/) is supported that can be used to convert any selected lines into comments (or back again).

When used well, comments can help keep the logic of your code clear to yourself and collaborators and assist in debugging. However, we recommend using them carefully and with intention, as commenting out an existing line of code can inadvertently affect other lines of code.

The 5 C's¶

When writing code for your experiment, keep in mind the 5 C's:

- Colon. Properties and values must always be separated by a colon.

- Comma. Any series of items must be separated by commas, but no commas may come after the final item in the series. This holds for both dictionaries (series of property-value pairs) and lists (series of individual values).

- Close (your quotes, brackets, and braces). Strings begin and end with double quotes

"". Lists begin and end with square brackets[]. Dictionaries and object definitions begin and end with curly braces{}. Always make sure that you include your closing quotation marks, brackets, or braces. If you don't, everything that follows will be treated as part of the prior string, list, dictionary, or object, which will likely cause an error. - Check (your code often). FindingFive allows unlimited code previews. The more often you check your code by attempting to preview it, the easier it will be to identify where errors are arising from.

- Comment (with intention). Comments are useful for organizing your code, making notes to yourself or collaborators, or ignoring sections of code without completely deleting them—which can help you identify the source of an error. But use them with intention, as commenting out lines of code can inadvertently affect other lines of code.

Breaking Down a Code Example¶

Note how the following definition of two trial templates ("Introduction" and "Task") adheres to the 5 C's:

| An example of the Trial Templates section of the study editor | |

|---|---|

What does all of this code mean? You could think of it like an outline, where information is organized at different levels.

- At the highest level, there is a JSON object representing all trial templates for this experiment, (implicitly) defined by the outer curly braces

{}.- Inside the object, there are two trial templates named

"Introduction"and"Task". - Within

"Introduction", there are two property-value pairs:- The

"type"property, with the value"basic". This is a required property for trial templates, and"basic"is the most common type. - The

"stimuli"property, with the list value["Intro_Text"]. Inside the list is a single object name (the string"Intro_Text") representing an individual stimulus object (defined elsewhere in the Stimuli section). Note that multiple stimulus objects could be defined here (that is why it is a list).

- The

- Within

"Task", there are three property-value pairs:- The

"type"property, again with the value"basic". - The

"stimuli"property, with the list value["stim1", "stim2", "stim3", "stim4", "stim5"]. This time the list contains 5 object names, each representing an individual stimulus object (defined elsewhere in the Stimuli section). - The

"responses"property, with the list value["resp1"]. Inside the list is a single object name (the string"resp1") representing an individual response object (defined elsewhere in the Responses section). Note that multiple response objects could be defined here (that is why it is a list).

- The

- Inside the object, there are two trial templates named

Conclusion¶

This concludes the tutorial Introduction to the FindingFive Study Grammar. Continue your learning journey by completing the Crash Course next!